On the morning of Friday 13 June, a few hours after Israel launched a volley of missiles towards Tehran, one of Donald Trump’s first calls was to the emir of Qatar. Trump hoped that Sheikh Tamim could persuade the president of Iran, Masoud Pezeshkian, to engage in a negotiated solution. Pezeshkian refused. Iran would be willing to talk, but would not negotiate under fire.

Over the next few days, during what has since come to be known as the “12 -day war”, the Qataris spoke regularly to President Trump and the Iranian leadership. “We were busy,” a senior Qatari diplomat told me, with some understatement. The risks to the region were high, but to Qatar they were “existential”, he said. Qatar is a tiny country. Most of its immense wealth comes from the undersea gasfield that it shares with nearby Iran, and the two nations enjoy good relations. At the same time, Qatar is a close ally of Iran’s greatest enemy, the US, and hosts the largest US military base in the region. If the US became involved in the war, Qatar would become a target.

Qatari officials immediately started looking, as the diplomat put it, “for ways to lower the temperature”. But on 22 June, the US struck three nuclear facilities in Iran. For the Qatari establishment, this escalation was a nightmare scenario. Yet within 48 hours, the conflict was over – and Qatar played a critical role in bringing it to an end.

On 23 June, Iran launched missiles towards Qatar, targeting al Udeid airbase, where 10,000 US troops are stationed. It was the first time modern Qatar had ever come under military attack. “I can’t believe this is Qatar,” said one panicked resident, in a video shared with me of the missiles loudly passing over her garden in Doha, the capital city.

Although residents of Doha were not forewarned, the strike was a carefully choreographed affair between Iran, the US and Qatar. Hours before the attack, Iran had informed the Americans that missiles would be fired at al Udeid. The Americans, in turn, briefed the Qataris, who closed their airspace in anticipation. Fourteen missiles in total were discharged, and all bar one were intercepted by Qatari defence forces. (The other landed in al Udeid but caused no casualties.) Qatar condemned the attack but did not retaliate. By allowing Iran a face-saving strike on US assets, Qatar “took one for the team to allow for de-escalation”, said Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, a Middle East specialist at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

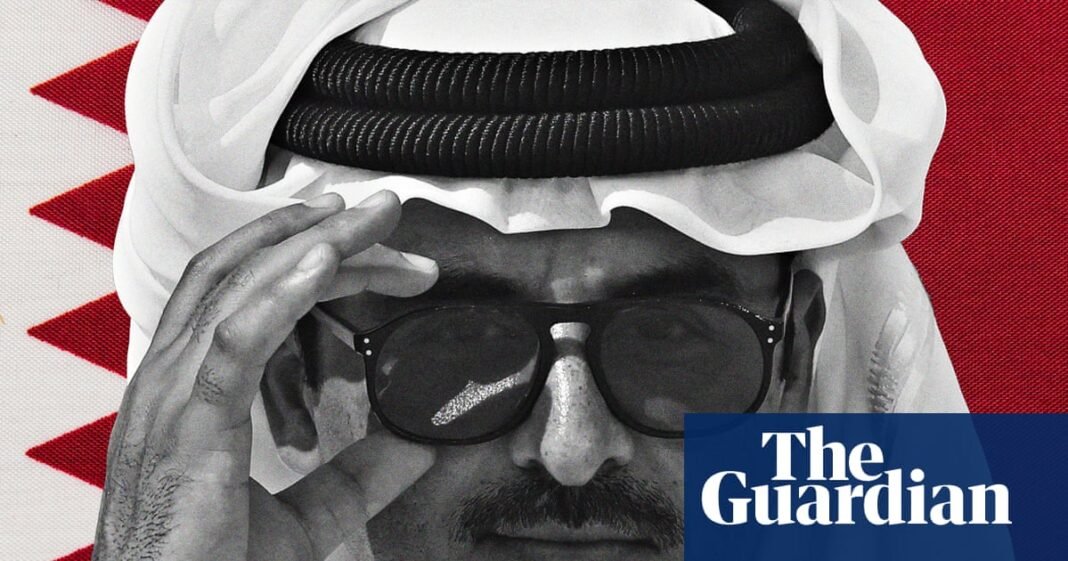

After the strike on al Udeid, Trump once again leant on the Qataris for help. In a call to the emir, Trump explained that Israel had agreed to a US ceasefire proposal – now he wanted the Qataris to help convince the Iranians to sign up to it. On 24 June, the Qatari prime minister, Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman bin Jassim al-Thani, secured Iran’s agreement to end hostilities. Qatar had helped to snatch peace from the jaws of war. It was an “upsetting” episode, the Qatari diplomat told me, and it was not “cost-free”. But even as the Qataris privately seethed at the strike’s disruption to its airspace and the way the missiles had unsettled its populace, in public the Qatari prime minister was calling for diplomacy.

Qatar is a rich country with a poor man’s mindset, a powerful country with a weak one’s vigilance. Its focus on diplomacy is an effort to shore up its fragile position, as a small nation in a volatile region, surrounded by swaggering players such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Iran. Its population is around 3 million, of whom about 13% are Qatari. (The non-Qatari population is largely comprised of migrant workers from the Arab world, the Indian subcontinent and the Philippines.) Wealth is concentrated in the small Qatari citizenry, who over the past 20 years have become the richest in the world. But all that wealth still cannot buy security. After I joked with one senior Qatari official about how hard they all seemed to be working, he responded with a weary seriousness. It would be great if they could all go home and enjoy the country’s prosperity, he said. “But we can’t afford to.”

And so, slowly, quietly, Qatar has made itself into the diplomatic capital of the world. Over the past year, I have spoken to more than two dozen sources, including senior Qatari government officials, western diplomats, local and foreign academics, residents and parties to negotiations mediated by Qatar. Over these conversations, and two trips to Doha, what emerged was a picture of a small country in a sprint to fill a big and rapidly growing role: global middleman. Dotted across Doha are the many palaces and offices that have hosted, over recent years, negotiations for the withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan, the return of Ukrainian children from Russia, the return of US hostages from Iran, the release of Israeli hostages held by Hamas and, earlier this year, a brief ceasefire in Gaza.

As of July 2025, Qatar is running 10 active mediations, some hosted in Doha, others abroad. On 28 June, Qatari officials were in Washington DC at the signing of a peace treaty between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda, the result of negotiations that Qatar had initiated earlier this year. A week later, I spoke to Dr Mohammed bin Abdulaziz al-Khulaifi, Qatari minister of state and chief mediator, a man with a dizzying travel schedule. After attending the peace treaty signing in DC, he had travelled to Venezuela, where Qatar has been acting as intermediary between the US and Venezuela as they discuss prisoner swaps and tussle over the deportation of Venezuelan migrants. A few hours after our conversation, Al-Khulaifi was poised to receive an Israeli delegation in Doha to start a new round of talks with Hamas. “Whenever there is a conflict or a crisis, you will see us,” he said, ushering people “to the negotiating table.”

The power Qatar has come to wield has taken many observers by surprise. As a conservative Muslim monarchy in the Middle East, Qatar is a new kind of location for the sort of high-stakes geopolitical deal-making transacted until recently in Geneva and Oslo. Yet since 7 October, the precarious nation’s investment in becoming the world’s go-between has come into its own. Having long cultivated close relations with both the US and Hamas, Qatar became the locus of ceasefire negotiations, as well as discussions over aid and evacuating the wounded. And as the conflict expanded into the wider Middle East and drew in the US, Qatar’s mediation has grown from a strategy to enhance its own safety into a role that underpins the entire world’s security.

As an independent nation, Qatar is only 54 years old. In its first decades after the end of the British protectorate in 1971, Qatar was synonymous with nothing at all: not the oil riches and religious power of Saudi Arabia, nor the construction boom of Dubai, nor the cultural and political reach of Egypt and Syria. In the 70s and 80s, white collar workers from across the Arab world migrated to the oil-rich economies of the Gulf. Few went to Qatar. Its ruling family, the Al-Thanis, had no profile. The country was seen as little more than a vassal of its larger neighbour Saudi Arabia. The first time many in the region even saw the Doha skyline was when the TV channel Al Jazeera launched in 1996. The Doha Sheraton, a lone squat building on the coastline, was all there was.

Then in the 90s, Qatar struck gas and everything changed. The South Pars/North Dome, which partly lies in Iranian waters, is the world’s largest natural gas field. Within a matter of years, Qatar became the world’s leading exporter of liquified natural gas (LNG), and its sovereign wealth exploded. During this same period, the Qatar we know today was taking shape. In 1995, Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani carried out a palace coup against his father, banishing him from Qatar until the early 2000s. Whereas his father had been happy for Qatar to remain subordinate to Saudi Arabia, the new emir had bigger ambitions.

The year after the coup, Al Jazeera was launched. In contrast to the deferential approach of state-controlled news media across the region, Al Jazeera took Arab political discourse out of the street and on to the airwaves, challenging orthodoxies, poking at sectarian tensions and antagonising other Arab governments. When Sheikh Hamad came to power, a person affiliated with Al Jazeera told me “he had a strategy of putting Qatar on the world stage”. The new channel was part of that plan.

While Qatar used the new channel to spread its cultural reach regionally, through the Qatar Investment Authority it expanded its financial power even further. In Britain, the country that once ruled over it, Qatari state institutions and private entities amassed a £100bn property portfolio, scooping up Chelsea Barracks in 2007, the Shard in 2009 and Harrods in 2010. In France, it acquired Paris Saint-Germain football club in 2011; in the US, Miramax studios in 2016; and in the same year, the iconic Asia Square Tower 1 in Singapore.

Its most audacious move, during this period, was securing the 2022 World Cup. As it prepared for the tournament, after winning hosting rights in 2010, Qatar was accused of subjecting migrant labourers working on construction facilities to conditions, particularly heat exposure, that caused hundreds of deaths. A 2021 Guardian investigation found that 6,500 workers had died in the previous decade. (Qatar responded with a dogged insistence that the criticism was simply unfounded, but nevertheless implemented labour reforms.) The tournament itself went off smoothly, and so elevated the nation’s global status that the Qatari prime minister described it as “Qatar’s IPO”.

The home of all these epic manifestations of financial power and political determination is a relatively subdued place. One can visit Doha many times, as I have over the past 15 years, and never feel you break into the heart of the country. Its centrepiece is not a skyscraper like Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, but a refurbished historical market of shops, cafes and performance areas where locals, tourists and expats mix. Evenings are quiet. And for such a small place, it can feel strangely cavernous. On a recent visit, I often felt like an awkward Little Lord Fauntleroy – sipping carrot juice in an almost entirely empty hotel lobby, or sampling a colossal breakfast buffet with so few other takers I began to think about the vast quantities that would soon be thrown away. In Doha, one is rarely in the slipstream of a crowd, apart from in the foothills of a mall, where shoppers wait for their chauffeured cars and Ubers. The few hundred thousand Qataris in Doha float above the fray, an identifiable upper class, the men in white and the women in black.

The contrast between Doha and its attention-grabbing neighbours is instructive. To the east is Dubai, which is far livelier but more like a park for the global super-rich. To the west is the Saudi capital, Riyadh, which is now open late, jettisoning religious convention on gender mingling, and courting the global fashion and entertainment elite, but still finessing how that sits with its traditional core. As they undergo profound transformations, these places feel somewhat uncertain of themselves. What is striking about Doha, and Qatar in general, is that rapid change has not been accompanied by the same identity crisis. It is conservative without being hardline (alcohol is tightly regulated for personal consumption but available in hotel bars), Qatari women are prominent in senior government roles but always in demure and modest dress. With its wealthy, small and religiously monolithic Sunni population, Qatar has no fears of revolution. “As much as we like to emphasise some of their vulnerabilities,” says Allen Fromherz, director of the Middle East Studies Center at Georgia State University, “I also think they are in a uniquely politically stable situation vis-a-vis their own population.”

This is perhaps why the Qataris are more comfortable turning Doha into a place where people come together to talk. The Qatar Economic Forum and the Doha Debates, two annual gatherings that make up a sort of Davos on the Persian Gulf, have been going for more than 20 years, and temporarily turn parts of the city into a hub of chatter and activity. There are limitations to the image the Qataris seek to project. Discourse is turned outwards, with Qatar as a sort of backdrop to global discourse, its own shortcomings and political decisions left uninterrogated within its borders.

Being a small nation, Qatar’s identity is largely defined by its political establishment. In a 2021 interview, the emir described Qatar as having two roles: “energy provider and peace facilitator”. The former is an asset deposited by virtue of geological fortune, but the latter is a concerted choice by the country’s leadership and pursued with increasingly single-minded determination.

Diplomacy is central to how Qatar sees itself. Its 2003 constitution explicitly states that Qatari foreign policy “is based on the principle of strengthening international peace and security by means of encouraging peaceful resolution of international disputes”. Spending time with Qatari officials over the past few months, I got the impression of a political establishment that seemed excited by the fact that an abstract policy pledge made more than 20 years ago had now become real. “This is a job that not many people do,” minister of state Al-Khulaifi told me. “Sometimes we feel like we are doctors, trying to develop the right solution for the most complicated cases, trying to offer them the medicine they need.”

The rewards Qatar seeks from this work are not immediate, tangible ones. They’re not looking for investment opportunities, access to raw materials or a say in what happens after a deal is agreed. “They don’t ask anything from the participants,” said one source who had recently been involved in a Qatari-brokered mediation process. The source’s counterpart on the other side echoed his comments: “All they wanted was to be recognised as a player.” The fruits of the brokering – building status and trust, which in turn deepen international influence and relationships – are the prize.

The top team that deals with global crises is small enough that they could all fit into an SUV. It includes the emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani, along with Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman bin Jassim al-Thani, who is both prime minister and foreign minister, and Al-Khulaifi, minister of state for mediation, disputes and conflict resolutions. According to one person familiar with negotiation arrangements, the emir often phones leaders personally to persuade them to start a mediation. This is how Qatar managed to get Paul Kagame, president of Rwanda, to fly to Doha in March to take part in peace negotiations with the DRC. Even when the emir is not in the meeting rooms, he is on an instant messaging hotline to those who are, and weighs in on big decisions.

“The Qataris play different roles at different points,” says Sansom Milton, co-author of a new book about the rise of Qatar as a conflict mediator. The first role is go-between: using its ability to talk to all parties in order to pass messages between often bitter antagonists. The second is persuader: convincing people to come together to hammer out an agreement. The third role is facilitator: that is, hosting the different parties and providing other services. Once at the table, according to one source with first-hand knowledge of the process, Qatari mediators often finesse and re-craft messages passed between negotiating teams, taking the edge off provocative language or unreasonable demands.

Underpinning all of this work – as go-between, persuader, facilitator – is Qatar’s role as a funder. Milton mentioned the way, in 2020, the Qataris were able “to fly in 400 Taliban delegates to Doha at short notice” to work on the final stages of the agreement for the US withdrawal from Afghanistan. Ten years earlier, Qatar helped convince rebels in Darfur to talk to the Sudanese government by promising hundreds of millions of dollars in post-peace agreement aid. One of the benefits of being an absolute monarchy with limitless wealth is that vast sums can be spent without having to clear lengthy bureaucratic or administrative hurdles.

Ask senior Qataris about the roots of their diplomatic work, and they will often refer to the country’s historical status as an underdog. Situated in a particularly harsh and dry patch of desert, for centuries all Qatar had to offer was shelter for groups that had been ostracised elsewhere, including political refugees and exiles. Qatar’s founding father, Jassim bin Mohammed al-Thani, famously referred to Qatar as “the Kaaba of the Dispossessed”, in reference to the stone building in Mecca’s Masjid al-Haram (Great Mosque), the destination of Muslim pilgrimage. Two hundred years later, that phrase was repeated by almost every person I spoke to as a distillation of Qatar’s ethos. According to this view, Qatar’s small size and awkward location are weaknesses that produced its greatest strength: an ability not just to ingratiate itself with the powerful, but also to identify with, and gain the trust of, the weak.

As with any national story, Qatar’s is partly a product of selective memory, wishful thinking, calculated PR strategy and so on. But a variety of sources across the political spectrum, including a US state department official, a Palestinian activist, and a western image-making consultant – each of whom had worked closely with the Qataris – all suggested that there is a perhaps surprising degree of principle and sincerity to Qatar’s politics. Azzam Tamimi, a Palestinian historian of Hamas who spent time with its political leadership in Doha, told me that even though Palestinians began seeking refuge all over the Middle East and Arabian Gulf after the Nakba in 1948, Qatar had a certain “extra empathy” with Palestinians that endured and extended into financial support for the Hamas government in Gaza, and refusal to normalise relations with Israel.

That position has not precluded engagement with Israel. In October 2024, Gershon Baskin, an Israeli political activist with extensive experience of negotiating with Hamas travelled to Qatar independently to work on a hostage release proposal. Initially, he said, he was “suspicious” of the Qataris, but found them to be “serious” and “sincere” in their efforts to bring about peace. He also said he was surprised, on checking in to his hotel, the Waldorf Astoria in Doha, to find Yossi Cohen, the former head of the Mossad, sitting in the lobby “with a group of businessmen”. It was a moment that revealed to him that Qatar’s role is not a binary one of simple loyalty to Hamas and enmity towards Israel, but something “more complex”.

Qatar’s sharp focus on diplomacy is partly the product of years of bitter conflict. In the 2010s, after long adhering to wider regional consensus, Qatar began to actively antagonise its neighbours. The trigger was the Arab spring. When the revolutions began, Sheikh Hamad was 15 years into his tenure as emir. Like many of his generation, growing up in the 1950s and 60s, he was inspired by the pan-Arabism of Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, whose charisma, fierce opposition to Israel and vision of the Arabs as a proud bloc of peoples united by their shared histories made him a regional icon. To Sheikh Hamad, the Arab spring protests evoked an old longing for self-determination that had been repressed for decades. Under his leadership, Qatar broke ranks with the other powers in the region by siding with the protesters, backing the revolution in Egypt, Syria, Tunisia and Libya.

Al Jazeera’s role in covering the Arab spring, which began in December 2010 in Tunisia, was central to this effort. Hugh Miles, the author of an authoritative book on Al Jazeera, told me that although the network is not a state broadcaster, it is “completely owned and controlled by the Qataris”, and its Arabic channel is often used to “advance their foreign policy positions”. Al Jazeera, he added, gave Qatar “enormous influence through the Arab spring”. The channel beamed footage of raging protests, vox pops and excited analysis to hundreds of millions across the region. In early 2011, graffiti scrawled on a Cairo wall captured the three forces that many saw as stoking the revolution: “Twitter, Facebook, Al Jazeera”. In February 2011, Egyptian protesters in Tahrir Square chanted “Long live Al Jazeera”. A week later, President Mubarak resigned.

The party around which revolutionary passions coalesced was the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, a longstanding opponent of established Arab regimes, and in June 2012, it won the first post-revolution election in Egypt. In just one year, the Qatari government offered President Mohamed Morsi’s government almost $8bn-worth of hard currency bank deposits, loans, and natural gas. This level of support merely deepened an existing relationship. In 1961, a prominent Muslim Brotherhood spiritual leader, Yusuf al-Qaradawi, was exiled to Qatar, where he developed close relations with the royal family. Al-Qaradawi was a popular televangelist and household name across the Arab World, as well as a controversial figure in the west, where he was banned from entry by, among others, the UK and the US for endorsement of suicide bombings in Palestinian occupied territories and attacks on American soldiers in Iraq. “The Brotherhood”, said Fromherz, who taught at Qatar University in the late 2000s, was “institutionalised” in Qatar. “Qaradawi received Qatari citizenship; his daughter was my dean.”

In June 2013, Prince Tamim took power in Qatar from his father in a peaceful transition. As a young emir, only 33 at the time he ascended to the throne, he could not be seen to be breaking with his father’s policies, a source close to the ruling family told me. That would have been to discredit Sheikh Hamad. So Tamim initially followed his father’s ethos. During the Arab spring, “We stood by the people,” Tamim told 60 Minutes. “They [Saudi Arabia and UAE] stood by the regimes. I feel that we stood by the right side.” After the military coup that toppled Morsi’s government in July 2013, Al Jazeera was the only regional channel that followed, live, the Muslim Brotherhood’s protests and gave airtime to others critical of regimes in the region. Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt were infuriated by what they saw as Qatar’s continued efforts to threaten their stability, as well as its continued close relations with Iran.

After years of threats, regional tensions came to a head in the summer of 2017. On 5 June, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Yemen, Egypt and Bahrain cut diplomatic ties with Qatar. Qatari vessels were prohibited from utilising air, land and sea across the Arabian Gulf and Egypt. Saudi Arabia closed off Qatar’s only land crossing. Meanwhile, Saudi and the UAE had mobilised troops and were poised to invade. “We felt that we had Trump by our side,” a Saudi source told the BBC, “so let’s finish this little country that’s been bugging us for years.” Only a last-minute intervention by US secretary of state Rex Tillerson, who knew the Al-Thanis well from his days as an executive at ExxonMobil, saved Qatar. Saudi and the UAE backed down, but the blockade continued. (Last year, in homage to the nation’s saviour, Qatar named its first conventional LNG carrier Rex Tillerson.)

Qatar was able to weather the blockade. One Doha resident recalled how, in-mid June 2017, it had seemed like all was lost: supermarket shelves had been emptied and there was little hope of replenishment. And then suddenly, they were full, this time with produce written in an unfamiliar language. Turkey had stepped in to fill the gap. “Süt,” the resident said, was a Turkish word that Qatari residents came to learn meant not just “milk”, but salvation. In the months that followed, Qatar flew in thousands of cows from Europe, Australia and California, shepherding them down the ramp of Qatar Airways airbuses. Qatar also began investing in its own food production. Before the blockade, 72% of Qatar’s dairy was imported. In November 2019, it made its first dairy export.

The blockade lasted almost four years, and Qatar emerged in 2021 having learned some important lessons. First, making big political plays in the open was a mistake: the parties that it very publicly supported during the Arab spring had been eviscerated, and the cost of alienating its neighbours was high. Second, the soft power of mediation, already a feature of its politics, needed to become central to how Qatar presented itself to the world. Third, it would no longer appear to pick sides. It would be a mediator for everyone. And fourth, Qatar needed to make itself indispensable to the nation that saved it from being swallowed by its larger neighbours. In 2017, Qatar was lucky that Tillerson occupied such a powerful position in an otherwise hostile Trump administration. If there was a next time, Qatar’s fate would not be left to chance.

Qatar’s success in winning over the US can be summed up in two statements by Trump, almost exactly eight years apart. In June 2017, Trump tweeted, “During my recent trip to the Middle East I stated that there can no longer be funding of Radical Ideology. Leaders pointed to Qatar – look!” In May 2025, Trump became the first US president to make an official visit to Qatar. “Congratulations on a spectacular job,” he said to the emir in a speech. “Let us give thanks for the blessings of this friendship. It’s an honour to be with you.”

The shift is the product of a concerted campaign. More than any other nation in the Gulf, Qatar is totally reliant on the US security umbrella. On a smaller scale, it seems to be approaching the Israeli model: a state with insecure borders that has sought to fortify itself by becoming a vital part of US security interests. The key part of this strategy is, without doubt, al Udeid airbase. It was built in 1996 at a cost of $1bn, after a joint military agreement between the US and Qatar, but it expanded over the years, most dramatically in 2018. Only 18 miles from Doha, it is discreet and self-sufficient, with a large shopping mall that stocks everything from protein bars to pork products. In May 2025, Qatari pledged to invest another $10bn. That cost includes everything from construction of runways, hangars, barracks and housing facilities to their maintenance and modernisation.

This is a big investment, even for Qatar, but its true value is incalculable. Any attack on Qatar puts American troops in the line of fire and threatens what has become the headquarters for US Central Command for the entire Middle East region. Al Udeid was the centre of “Operation Roundup”, which dismantled Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. Along with US troops, the base also houses hundreds of Nato troops.

In addition to al Udeid – which a Qatari official made sure to remind me was a Qatari base that hosts foreign troops, rather than a foreign base on Qatari soil – since 2017, Qatar has done two key things to ingratiate itself with the US: with its diplomatic work, it has strived to show what a useful ally it can be in a turbulent world. At the same time, it has assiduously wooed the American financial and political elite. In both cases, it has spent a lot of money doing so. Ben Freeman, a research fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, who focuses on foreign lobbying in the United States, told me that less than a decade ago, Qatar was “an afterthought”, as far as US foreign policy went. Today, it is “riding high”.

In the summer of 2017, to counter more established UAE and Saudi lobbying networks, Qatar moved quickly. “Literally, within days, if not hours, after the blockade began,” Freeman told me, “they really go on this spending spree.” By 2018, according to analysis of Foreign Agents Registration Act records, 33 entities, including firms and individuals, were representing Qatari interests.

Qatar made sure to connect with Republicans close to Trump. In 2019, it hired Pam Bondi, Trump’s current attorney general, to provide consulting services. In 2021, shortly after he left his position under the previous Trump administration, Qatar hired Kash Patel, current director of the FBI, to provide consulting services. In March 2025, Qatar hired US lobbying firm Cornerstone Government Affairs. Working on Qatar’s account are David Planning, a former special assistant to Trump, and Chris Hodgson, a former aide to former vice-president Mike Pence.

Since 2023, the Qatar Investment Authority has ploughed hundreds of millions of dollars into Jared Kushner’s investment company. In 2023, Qatar also spent more than $600m buying out Steve Witkoff and his partners’ investment in a troubled development project. Witkoff is now Trump’s Middle East envoy, and earlier this year gave an interview to Tucker Carlson in which he spoke effusively about the Qataris’ mediation work and described Sheikh Mohammed, the prime minister, as “a special guy”. Most famously, in May of this year, Trump was offered a $400m jet dubbed “a palace in the sky”. (Again, a Qatari official was at pains to remind me that it is a government-to-government transaction, rather than a personal gift.)

Meanwhile, Qatar continues to spend lavishly on US military equipment. In terms of foreign military sales, as distinct from military aid, Qatar is the US’s second largest partner in the world. (The largest is Poland, the US’s security partner against Russian aggression along the eastern flank of Nato.)

The transformation in Qatar’s relationship with the US – and the methods through which this has been achieved – have not gone unnoticed. Qatar’s mediating role between Israel and Hamas has triggered even more scrutiny, with one American outlet raising concerns over whether an “Islamic safe haven” could be “pulling the strings” in Washington and “buying America”. Another prominent US media outlet called for shutting down and relocating al Udeid, because the base served as an “effective means for convincing American policymakers to ignore [Qatar’s] mischief” as a “state sponsor of terrorism”. Witkoff has came under fire for his closeness to Qatar, and has responded by fiercely re-stating his pro-Israel credentials. “I am no Qatari sympathiser,” he told the Atlantic.

The accusations of being motivated by Islamic extremism or an anti-Israel agenda are, one Qatari source said, “a headache”. (Hamas opened an office in Doha in 2012. The Qataris assert this was not an endorsement, but the result of a request from the United States, which wished to establish a line of communication with Hamas.) Qatari leaders are confident that actions speak louder than words, and that they are proving their credentials as an honest broker. According to one senior Qatari official, the emir’s instruction to them when coming under “baseless criticism” is “close your ears. Focus on the main task and ignore them.”

In a world of accelerating conflicts and, under Trump, increasingly transactional foreign policy, Qatar now finds itself in a position where there is more appetite for its services than it can handle. Al-Khulaifi, the chief mediator, told me that Qatar is now receiving several requests for mediation – three in June alone – rather than initiating them. Majed Al-Ansari, adviser to the prime minister and spokesperson for the foreign ministry, told me that it’s an asset to have a small executive team, as Qatar does, because it means decision-making is quick.

But there are limitations to this setup. One US negotiator spoke of a “capacity” issue. It is common for senior Qatari officials to have more than one position, and demands on them have sharply increased. The emir, one senior Qatari official told me, seems to have aged 20 years in the last two. Al-Ansari and Al-Khulaifi told me that Qatar is in the process of expanding its mediating sector: hiring more people, employing experts and creating joint ventures with European mediators such as Norway. There is a desire, said Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, to rely less on the “personal relationships and Rolodex” of the leadership.

Qatar’s small size and big role means that sometimes matters have to be outsourced, which has led to political fallout. Earlier this year, two close advisers to Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu were arrested for taking money to promote Qatar’s image within Israel, resulting in what came to be known as Qatargate, a scandal that engulfed the Israeli government and security establishment. Qatari officials claim that the arrangement with the Israelis was secured, without their involvement, via a third party – a lobbying firm in the US tasked with burnishing Qatar’s reputation abroad. The Qataris say that the whole affair has become supercharged because of the war in Gaza and Israel’s polarised domestic politics, and because of a kneejerk mistrust of Qatar. Still, no country wants its name before a “gate”. And if the whole episode was indeed the result of a lobbying drive on which the Qataris had no oversight, that also suggests there isn’t enough capacity to manage Qatar’s expanding role in foreign affairs.

The various Qatari officials I spent time with oscillated, sometimes in the same breath, between self-assurance and humility. They were enthused, proud, even a touch evangelical about Qatar’s success in what they often referred to as “sadd al-fajwa”, meaning “closing the gap”, between belligerents. At the same time, they constantly restated the limits – sometimes plaintively, other times with a hint of frustration – of what a mediating power can actually achieve. It can’t exert pressure on parties and it can’t force people to agree if they don’t want to. They were aware of Qatar’s growing stature as a global political player, and yet constrained by what they see as the hallmark of a good mediator: never making it about yourself.

“Statecraft,” observed Middle East expert Andreas Krieg, “is about generating power or generating influence. Mediation is only good as a means of statecraft when you can extract influence from it.” Qatar has generated a lot of that power in recent months. Now it must deploy it not only to maintain its own safety, but global stability. The world has changed too quickly, too unexpectedly, and Qatar’s role in it is now bigger than it ever bargained for.

On 21 July, I spoke to an official with knowledge of the ceasefire discussions between Israel and Hamas. The previous day in Gaza had been particularly bloody: 93 people waiting for food had been killed by Israeli forces. Tense talks had stretched into their third week without breakthrough, but also without breakdown. Two buildings, a 10-minute drive apart, housed the Palestinian and Israeli negotiators, who had been briefing aggressively against each other in the international press. The Qataris shuttled between them, late into the night, ears closed, eyes on the prize.