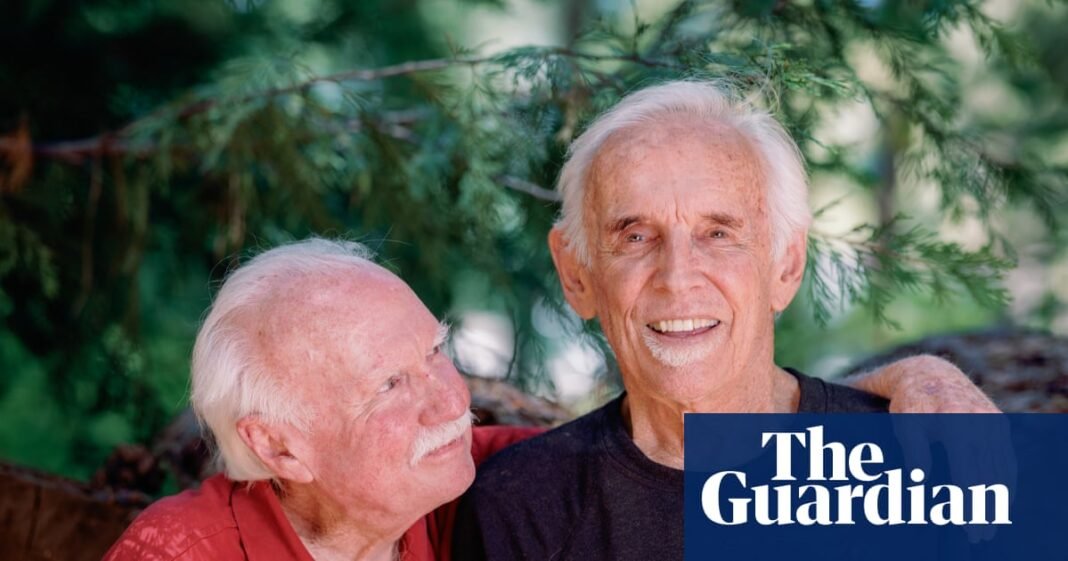

“What happened?” Scott, 82, asked Bruce, 78, when his younger brother picked up the phone and called him after a 15-year estrangement. “I grew up,” Bruce said. “I’ve been stupid and I really miss you.” The brothers had missed a decade and a half of each other’s birthdays, milestones and memories made, but here they were, talking again as though no time had passed.

A quarter of the adult population describe themselves as estranged from a relative; 10% from a parent and 8% from a sibling, according to research by Karl Pillemer, professor of human development at Cornell University and author of Fault Lines: Fractured Families and How to Mend Them. But when decades pass and rifts remain unhealed, what drives family members such as Scott and Bruce – or, rather more famously, the Gallagher brothers – to repair their ruptured relationships?

As children, in San Fernando valley, California, Scott and Bruce were close. “He was protective and a great storyteller,” Bruce says. “We’d go to the movies together and I remember hiding behind a seat at the cinema watching The Blob and waiting for Scott to tell me when to come out. We got along pretty well.” Scott had dyslexia and struggled at school, gaining less affection from their unemotional parents as a result. Bruce noticed: “He was undervalued. Our parents never acknowledged or celebrated his achievements.”

As they entered teenage years, these differences began to come between them. “We started to have issues when I began having my own opinions,” says Bruce, now living in Santa Fe. “I was and still am a know-it-all. I was thin-skinned and not very self-aware.”

Bruce gained a PhD and worked as a substitute teacher near Berkeley, California, while Scott became a screenwriter, got married, brought up two daughters and moved to Nevada City. The brothers met up a couple of times a year but Bruce remembers, “He would always say extremely hurtful things.” The comments festered until, during one trip in 2005, when the pair were around 60, Bruce “blew up”. “I’d bought us all seafood,” he remembers. “At the end of dinner Scott said, ‘This kitchen was clean, now it’s dirty – you should clean it up.’ It could have been anything but feeling belittled in front of my then girlfriend, it was egregious to me.”

So he cut ties. Their late father had also been a screenwriter and when Scott sent a cheque containing his regular half of residuals, Bruce returned it: “I didn’t want any more connection. It was too painful.”

“He never said he had a problem with me but it was clear,” Scott remembers. “I wasn’t deeply wounded. I didn’t have time to dwell on what was going on with him. I had to work and feed the family.” He imagined they would come back together someday and wondered, from time to time, if his brother was well. Bruce was “just glad to be out of the line of fire. I don’t remember missing him.”

But in 2020, Bruce felt ready for change. Some years earlier he had turned down a suggestion from Scott’s daughter that the pair reconnect but, with the world in lockdown, he began thinking about his relationships. “I realised I’d been too judgmental. I’d never walked a mile in Scott’s shoes. He was saying cruel things to me because I was being an ass. I was the jerk in this story.”

Bruce sought advice from a psychotherapist friend about how to reconcile, then picked up the phone. When Scott heard his voice again, he remembers, “We picked up exactly where we left off. There was no animosity. It was guilt free. We haven’t had a harsh word since.”

They called each other every fortnight. “We had a hard time hanging up,” Bruce says. Six months later, he went out to visit and has done several times since. “We’ve spoken a lot about our parents, who were kind and bright but not loving,” Scott says. “Neither of us remember being kissed or hugged. Talking about it has allowed us to rediscover each other and ourselves.”

Their time apart brought unexpected positives: “We have realised we’re similar in many ways. We think the same and have many of the same expressions. When we belly up to the bar together, you’d know we’re brothers,” Bruce says. He feels vastly happier: “I don’t feel I lost anything. In fact, it’s brought us closer than ever.”

Scott agrees: “It’s all been a gain.”

PIllemer says Bruce and Scott’s story is typical. “Common to most estrangements is a ‘volcanic event’ where pressure has built up to a single trigger, the capstone in a history of conflict or communication problems. Understanding what it signifies helps figure things out.” Those who reconcile go through a similar process, he adds. “There has usually been some self-exploration. Often, they come to realise they played a part in the rift.” A contemplation phase follows: “I call it anticipatory regret. They miss the person and start to think, if they don’t do this, will it be too late?”

For Oliver, 62, a family bereavement made him reassess the 28 years he had spent apart from his twin brother Henry (not their real names). “I remember thinking: what if he suddenly died and I never had the chance to talk to him? I picked up the phone and counted down: 10, nine, eight, seven … thinking: shall I do it?”

The two were nonidentical and had always been different: “As twins, there’s a presumption that you’re cut from the same cloth. But he had his friends and interests, and I had mine. He was intellectual and introverted, and I was the opposite, more colourful.”

By their teenage years, Oliver says, “We were just two brothers living in the same house. There was a distance between us. It was hard to connect.” They moved to different cities and, at 21, Oliver emigrated. “Whenever I came back, I would suggest we meet. I felt it was always met with an excuse.”

When Henry married, Oliver says, “I didn’t want or expect to be his best man and he didn’t ask. I just felt like a guest.” They headed further in different directions, speaking every few months until the early 90s when, on another trip home, Oliver asked Henry to dinner and found his excuse too painful: “It was always me initiating things; he didn’t once pick up the phone and ask how I was. Rejection is never easy but with family it hits harder.” Despondent, he thought, “OK, I’ve tried.”

In the almost three decades that followed, no one in the family addressed the twins’ alienation: “My parents knew but they didn’t say anything; I kind of wish they had.” Oliver says he wanted to connect many times, “but thought I was setting myself up for rejection. I learned from family members he was suffering with his own problems. There were things I wished I could share.”

When, in 2009, their sister’s husband died from cancer, Oliver returned to the UK for the funeral. The brothers found themselves in the same room again. “I saw him walking up to the house. I thought: this is going to be uncomfortable for everyone.” They didn’t speak but Oliver recalls, “His wife asked, ‘Do you think you’d consider calling him? I think he’d respond favourably.’” He flew home reflecting on her words and the shortness of life: “We don’t get to choose another family.”

A few days later, he called Henry. “It was like going on a first date. When we spoke I realised it’s not the point to talk about what happened, why you did this or said that. I thought, no, we’re going to leave that in the past; we’re going to talk about the present and future.”

Oliver called Henry every month: “Part of my thought process was about accepting him for who he is and not who I want him to be. He doesn’t talk about emotions whereas I’m very open. So I will pick up the phone and ask how he is because I want him as part of my life.”

Henry went out to visit Oliver and now, when Oliver comes back to the UK, he stays with his brother and has got to know his niece and nephew, too. “There’s no emotion, but I have peace with that. I accept him for who he is and it’s fine. We were in the womb together, we have a 62-year connection: you can’t deny that.”

While estrangement from siblings – or close cousins, grandparents, aunts or uncles – is upsetting, cutting off a parent or child is especially hard. “We are less obligated to be in touch with siblings, but we are bonded to our parents,” Pillemer says. “It is quite a big thing to say I never want to speak to you again.”

That is what happened to Choi, a 45-year-old digital marketer and DJ who grew up in a God-fearing Korean immigrant family in Buenos Aires. As a boy, he feared his father. “He was frequently physically abusive,” Choi says. “My sister and I would count how many days he’d been quiet, then he’d snap. I felt I was living in a prison.”

At 17, Choi tried to kill himself; at 18, when his father locked him out for missing a curfew, he left home. “If I’d stayed it would have been the end of me, so I turned around, with no money and no prospects, and never said goodbye.”

He was relieved to escape his father’s control, but missed his mother – the two were forbidden

to talk and over the next two decades saw each other only a handful of times, at Choi’s sister’s wedding and when he visited her, alone, at his parents’ shop. “When I went we’d have a few minutes. She’d ask a lot of questions but we couldn’t have a serious talk. She would ask me to come back and apologise to my dad. I’d walk out feeling angry with her for expecting that of me.”

So he stopped visiting; for 10 years, they didn’t see each other at all. Then, in 2022, Choi says, “I wanted to reconnect. My then girlfriend had cancer during the pandemic, so it was tough. When she recovered, I felt grateful and started to think about Mum and Dad.”

Choi drove the four hours to his parents’ home and knocked on their door. “When Dad saw me he asked Mum, ‘Who is this?’” Choi remembers. “It was strange but not sad. I was mentally prepared for anything.” His father yelled at him, presuming he wanted money or somewhere to stay. “When his rant ended I told him, ‘I just wanted to see your face and say hello.’ They invited me in and he interrogated me, but I was happy.”

Choi began calling every Saturday. Conversations were “transactional”; occasionally his father apologised for his behaviour. “I told him I was also a bad son. I said, ‘Let’s not talk about the past, let’s try to build a new relationship.’” But on his next visit, a few months later, his father’s mood changed; he grew angry, then stopped answering his son’s calls. A year later, on a Tuesday morning in February 2023, an unknown number flashed up on Choi’s phone: “It kept calling so I answered.” It was the police station in his parents’ town. “My mum was there. She’d left him and asked if I’d go to get her.”

after newsletter promotion

Choi brought her to live with him. “She cooked for us and we ate together. I got her a phone and she called family in Korea she had also been cut off from. She told me about how my father treated her and controlled everything, about his outbursts and how hard it was.” A month later, the unknown number flashed up again. “I knew,” Choi remembers. “He’d killed himself.

“It’s hard to grieve a person like my father,” he says. But the death represented a moment of “deep change” – one that allowed Choi to rebuild his relationship with his mother. She moved back into the family home but the pair continue to visit and speak three times a week. “Our relationship is complex and still challenging; I want to protect her but I’m still angry about the past. She says, ‘You have to let go’ but it’s not easy.” He admires her for leaving and, above all, “I’m grateful to have her in my life. This is a second chance.”

Reconciliation is not the right choice for everybody, Pillemer warns: “There are situations where the relationship is dangerous or so damaging that it can be better to cut off contact.” And not everyone who attempts it gets the immediate response they had hoped for. “The most successful strategies are where they don’t give up completely and leave a door open.”

When the path to reconciliation opens up, gathering information about the person from family members can be helpful. Turning up unannounced is riskier and “not always the best approach” but for Grace, 55 (not her real name), who went 35 years without seeing or hearing from her father, it was life-changing.

Grace was 10 when he had an affair and left: “He went off to start a new life and I never saw him again. He didn’t seem interested in me and we didn’t have a strong connection. My mum, who was loving towards me, held a lot of animosity towards him and I felt I should hate him, but I didn’t.” She remained close to relatives on his side of the family who “went out of their way to make sure my feelings weren’t hurt by mentioning him”. Their paths never crossed. It was “a strange situation to be in” and the burden of being the girl, then woman, who didn’t speak to her father was “draining”.

Grace spotted her father fleetingly 20 years later when, aged 42, she gave a reading at her grandfather’s funeral. “I expected seeing me would stimulate something in him but it didn’t. I was a bit crestfallen.”

Two years after that, while driving with her cousins through the town where he happened to live, one pointed to the roadside. “There were two men chatting with newspapers,” Grace recalls. “‘There’s your father,’ my cousin said. ‘Oh yeah,’ I replied, but I didn’t have the faintest idea which was him. It really threw me.”

Grace realised she was hungry for information about who he was and traits they shared: “It was the elephant in the room for so long. The longer the avoidance went on, the bigger it became. I wasn’t sure how I’d feel and I was also convinced Mum would see it as a betrayal.”

The thought stayed with her until a couple of years later, going to a family wedding in Ireland, where her father now lived. Everyone was there but him. The next morning, without time to overthink, Grace walked to his house and sat on the doorstep: “I thought, if I go away now, I’ll never come back.” She didn’t have to wait long. When he returned, he didn’t recognise her at first. “Then he said, ‘You’d better come in. Do you want a cup of tea?’”

They sat at the kitchen table. “It felt surreal. I knew that if we were to have a relationship, uncomfortable topics were not to be broached. We talked about baking, feeding the birds, growing vegetables and his English pension. He asked if my mother was alive and I said, ‘Yes, she’s fantastic.’ I felt I had to fight her corner. That’s the only time we approached anything sensitive.”

Overwhelmingly, the feeling was of relief. “I needed to get rid of the feeling that part of myself was somehow amputated,” Grace says. “As I was leaving, he hugged me and cried a little. That felt satisfying.” They settled into a pattern of Christmas cards, birthday phone calls and visits once or twice a year, always lasting an hour.

She has thought a lot about why she sat on her father’s doorstep that day. “A lot of things in my life had come about through the actions or wishes of others,” she says. “I was no longer willing to be deprived of knowing my own father because of what that might mean to them: the possibility of hurting my mother, being rejected by my father or drawing relatives’ disapproval. And I couldn’t hold anyone else responsible for the rift when I was the only one capable of taking the necessary step.”

She wishes she had done it sooner: “I’ve had problems over the years dealing with crap from my childhood. Knowing he was just a normal person and I wasn’t insufficient in some way could have helped.” Her father is in his 80s now and Grace says, “It’s given me the opportunity, late in the day, to be his daughter. If he had died and I had never regained contact with him, that loss would have been awful.”

For some, reconciliation does wait until the end of life. Pillimer has found that, in cases of deep, unresolved harm, these moments can have negative consequences. “But when sincere and mutually desired, they can bring emotional closure, reduce regret and ease the grieving process for the one left behind.”

It was a deathbed conversation with her own father that eventually delivered closure for Lynne, a 71-year-old lawyer based in Independence, Missouri, after the pair spent more than a decade estranged during her teens and early 20s. She was 36 when he died, aged 59, but she says, “It was not until my dad was dying that we talked about the years spent apart.”

Lynne’s parents divorced when she was eight and her father moved out. “I remember seeing him regularly at first,” she says. “Then, when I was 13, my mother remarried, to a difficult man with several children of his own. We all moved in together. My father had problems paying child support for me, my brother and sister, so my stepfather forbade him from seeing us.”

She felt her father’s absence: “Things weren’t good at home. I remember thinking I just want a boyfriend to hold me when I cry. When I was older, I realised it was my father I’d wanted. In my teens, my mother made an offhand comment – ‘It’s good your dad’s not around, it makes it easier’ – and I thought: you are so wrong.”

Her mother’s new marriage lasted four years but the schism with her dad continued. In her late teens, Lynne turned down an offer, via a friend, to meet him. “I was still somewhat bitter,” she says. When he had a heart attack soon after, she didn’t visit: “I feel bad now but I was resentful that he hadn’t fought harder to be in my life.”

They did see each other when she got married, aged 21. “I didn’t want to get married without him there, so I invited him as a guest. He didn’t walk me down the aisle but we spoke, he gave me a gift and we hugged.”

Three years later, she made contact again, impulsively, on Father’s Day: “I saw a card and sent it. I’d never done that before and don’t remember what prompted me.” That December, he called on her birthday. Then they arranged dinner with her siblings. “It felt warm and accepting, but we didn’t talk about what had happened.”

Her dad had remarried, meaning Lynne now had a half-brother, and she and her father grew close again. She, her husband and son spent Christmases in Florida, where her dad lived. He visited them, too. “I discovered my father was very intelligent and his sense of humour was a little bit off, just like mine.”

She often imagined what it had been like for him during their years apart but received answers only in his final days. He suffered a pulmonary embolism and Lynne and her siblings travelled to upstate New York, where he had moved, to be by his bedside. “They told us he had 10 days to live,” she remembers. “We laughed a lot and talked. He apologised for his absences. He told me the divorce had been his fault, he’d cheated, that he was proud of me for becoming a lawyer, and how much he loved me and regretted what had happened. I was sad he was dying but this felt like the best thing to come out of those circumstances. It provided a lot of closure.

“Some relationships never heal, and some people are despicable, but that was not my situation,” she adds. “I’ve always thought those who hold grudges or stay resentful harm themselves most. It’s so much more freeing and life-affirming to forgive.”

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on freephone 116 123, or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, you can call or text the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on 988, chat on 988lifeline.org, or text HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at befrienders.org